|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 5, 2024 16:59:18 GMT -5

Former Yankees Bonus Baby Reserve 1B Frank Leja (1954-1955)

This article was written by Evan Katz, Edited by Clipper

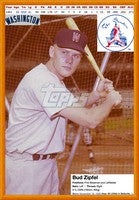

1955 Topps BaseballCard

The day the Yankees won Game 2 of the 1953 World Series, 17-year-old Frank Leja was in New York signing a contract that made the sports pages across the country. The 2nd-youngest Yankee ever reportedly received a $100,000 bonus. But like many mid-1950s “bonus babies,” Leja was a victim of the revised “bonus rule” of 1952, which required free agents signed for more than $4,000 to remain on a major league roster for 2 years. Successes like Al Kaline and Sandy Koufax were rare and Koufax took several years to break through.

These stars overshadowed the teenagers and college players who could not meet unrealistic expectations, were improperly developed, or worse.

Yankees Manager Casey Stengel would look down the dugout bench and call, “Leej!” Leja would stand up and ask what Stengel wanted and the skipper would say, “Nothing. Just sit right there.”

And that’s what Leja did for 2 seasons until he met his roster requirement. The 1st baseman got into just 19 games as a Yankees player and made merely 7 plate appearances, while playing in the field for 12 innings. He was sent to the minors in 1956 and it took 6 years and over 1,000 games to return to the top level with the Los Angeles Angels. In 7 games later, his MLB playing career was over.

Leja was 1 of the 3 best players, who never made it big in the major leagues, 7-decade Red Sox Player/Manager/Coach Johnny Pesky told Leja’s son, Frank Carl.

Frank John Leja (the family name is Polish) was born on February 7,1936, and grew up in Holyoke, then a thriving mill city on the Connecticut River in west-central Massachusetts. Leja and his younger sister Louise lived with their father and mother, Frank Sr. and Julia (Wojtasczyk). His father was an auto parts salesman and his mother was at home. The Lejas were renters in neighborhoods of single and multi-family homes in Holyoke.

Leja started playing organized baseball at age seven.5 Louise said that while they were growing up, her brother asked her to throw him grounders in their packed dirt backyard. In junior high school in the late 1940s, Leja was coached by Holyoke native Ed Moriarty, a former Boston Brave. Moriarty encouraged Leja to give up switch-hitting and hit left-handed.

Holyoke High School was in the middle of a 10-year period (1944 to 1953) when it advanced to the state baseball finals 5 times. In 1953, Leja’s senior year, Moriarty coached the high school team. That squad included pitcher Roger Marquis, who played 1 game as an outfielder with the Baltimore Orioles in 1955. Holyoke won the state championship for the 2nd time in 4 years. Leja, who had grown to 6-feet-4 and 205 pounds, led the team at the plate in his senior year.

With only 200 boys at 1,000-student Holyoke High, Leja had played and excelled in football, basketball and baseball. A football injury in his junior year encouraged him to concentrate on baseball, especially with the prospect of an immediate pro baseball signing bonus. He struggled at the plate as a sophomore and junior, hitting below .225 both years, with a total of 9 extra base hits and 10 RBIs. His breakout year as a senior, 1953, brought the MLB scouting spotlight to Holyoke. With hits in all 21 games, he had batted .432, with 5 HRs, 5 triples and a double. He had 22 RBIs and 19 stolen bases. His solo HR in a 1-0 sectional playoff win propelled Holyoke to the state championship.

Holyoke High Principal Harry Fitzpatrick said Leja “was a good student, always a gentleman, quiet, unassuming. He was liked by students and teachers. He was intelligent and mature for his age…He’s a star athlete but beyond that, a true sportsman.”

“The 1st one at practice, the last to leave the field,” said Moriarty. “He’d stay there until he perfected his fielding.” That made the left-handed throwing Leja more than a 1-dimensional slugger. He was inspired by Stan Musial, also of Polish descent, who played the position frequently.

Leja graduated on June 15th and deferred matriculation to Dartmouth College, where the baseball team was coached by former Yankee All-Star 3B and Detroit Tigers Manager Red Rolfe. Rolfe advised Leja to showcase his talent, because a bonus might disappear, if his baseball career foundered in college.

The next day, on June 16th, Leja was in the Polo Grounds with the New York Giants. During the next 2 weeks, he would visit Milwaukee, Chicago and Boston, working out for the Braves, White Sox and Indians (who played the Red Sox in Boston from June 23rd-25th).

The Boston tryout was reported in the Boston Traveler and included a picture with Indians Manager Al Lopez, who was quoted in the caption that Leja would be Luke Easter’s successor at 1st base. When the Indians traveled from Boston to New York in late June, Leja was directed to report to Commissioner Ford Frick’s office.

“I got grilled,” Leja said. “But there I was, 17 years old and what did I know about baseball laws. I just wanted to play ball. I was scared in that real big office, with Frick asking and somebody writing all that stuff down. It was like I was a criminal.” When Frick inquired whether Leja had been given gratuities, Leja asked what those were. Frick snapped, “Gifts, money, spikes, gloves, things like that?”

Leja explained the Indians gave him meal money and a glove “because I only had a high school glove. I wasn’t from a wealthy family.” And Leja reported they said, “That’s it!”

The Commissioner had fined the Indians, Braves and the Giants for tampering. It was a national story; Leja was declared ineligible and could not be signed until September 10th. He was suspended from playing American Legion baseball but he was reinstated after submitting an affidavit stating he had not been negotiating with the teams.

In September, tryouts would resume. On the 29th, the day before the World Series began, Frank and his father began final negotiations with the White Sox, Indians and Yankees in New York. The White Sox didn’t want Leja to sit on the bench; he refused a minor-league deal. The Indians would rejected Leja’s proposal for an $85,000 bonus. Then the Lejas met with Yankees General Manager George Weiss and the club’s legendary MLB scout, Paul Krichell, who found Leja and described him as “another Lou Gehrig.”

Leja’s $25,000 bonus was far less than speculated ($100,000) and he had agreed to keep the amount confidential. “This is an opportunity that’s here now,” Leja reflected. “I can get my education later.”

“I was always waiting for the Yankees,” said Leja. “There’s something different about them. You put their uniform on and you want to work your fingers to the bone.”

Manager Stengel said, “He’s the most experienced 17-year-old I ever saw. After all, he’s been around both leagues [trying out]. I like the boy.”

In October, the Yankees had sent Leja to Puerto Rico to play winter ball for Harry Craft (Manager of New York’s Triple-A team in Kansas City) and the San Juan Senadores. Leja later recalled, “After 2 months I started getting sick of the same routine: 5 cuts, shag, then sit on the bench and cheer while other guys played. I played 3 games in about 3 and a half months and learned nothing.”

At spring training in 1954, the pattern repeated. “I’m going to play you,” he remembered Stengel saying. “[Johnny] Mize [the backup at 1st base] is gone and we need a 1st baseman.”

But Leja had already slipped on the depth chart. Originally touted as backup to Joe Collins at 1st, Leja was displaced by veteran Eddie Robinson, who was acquired in December. Then another 1st baseman, Moose Skowron, made the team out of spring training.

When Leja got his 1st paycheck in April, it was based on 1953’s major-league minimum salary of $5,000, not the $6,000 minimum in effect for 1954. Leja raised this discrepancy with AL player representative Allie Reynolds, who bumped it to the front office. The issue then landed before Commissioner Frick.

“What the hell is this about your contract?” Frick asked Leja at major-league headquarters.

Leja replied, “I should’ve signed a new contract with an update on the ’54 minimum salary.”

Frick responded, “What the hell are you talking about? They have paid you enough money. Now get the hell out of here and back to the stadium.”

Leja relented, but the Yankees did not forget. The front office stopped communicating with him. “I had the feeling, from that point on, I’m in deep trouble here.”

In 1954, Leja would never started a game. At Fenway Park, Red Sox left fielder Ted Williams said, “Hey Leej! They’re really screwing you, ain’t they?”

On September 19th, Leja was inserted as a pinch runner against the Philadelphia Athletics with none out in the 8th. The Yankees scored 4 runs and turned over their lineup. With 2 out in the 9th, he singled for his solitary MLB hit.

At spring training in 1955, Stengel observed, “Leja’s a different player this year. He’s more mature, more relaxed around the bag and at the plate. He felt he was excess baggage last season, which he was, of course, but he’s learned a lot.” Leja was joined by another bonus baby, infielder Tom Carroll, as the Yankees allocated a 2nd roster spot to a teenager. Stengel said, “You know, I’ve told both kids they have the same opportunities [Mickey] Mantle had when he made the jump from Joplin [Missouri]. They’ve both got what it takes.” But 1955 was no different. Leja never started a game. In the World Series, the Yankees would not even let him take batting practice. In 2 years, 19 games; 10 as a pinch runner, 5 as a defensive replacement, 4 as pinch-hitter, 7 at-bats with 1 hit.

Leja said his teammates treated him well, despite practical jokes and ribbing. Upon his arrival at spring training in 1954, he found all of his equipment labeled with dollar signs where his name should have been. Yogi Berra said he wanted to room with “Money” (and he did on the road for 2 years). Some players called him “The Dude” because he bought $15 sport shirts. “During my 2 years of bench-warming, my teammates treated me fine,” said Leja. In 1955, they had voted him a full World Series share. The Yankees’ experiment with Leja ended in 1955. One analysis of the signing and development of bonus babies in the mid-1950s gave the Yankees an “F” for not allowing either Carroll or Leja to play.

Leja’s demotion to Triple-A Richmond in 1956 at age 20 was expected, but being dropped to Single-A Binghamton and then to Class B Winston-Salem was not. Pitcher Eli Grba, who played with Leja, remembered how clubs handled players who did not conform to team norms. He said, “If you screwed up real bad, even if you hit .310 and had 25 HRs in AAA or AA, they’d send you down.”

Leja had 36 homerless at-bats in Richmond, hitting .222. At Binghamton, he hit 6 HRs with a .242 average in 43 games; with no warning, Leja said, he was demoted again. He went home for a week, then reported to Winston-Salem, where he hit .216 in 65 games. Leja said he was demoralized and just “went through the motions” for the rest of the season.

Back in Binghamton in 1957, still 3 years younger than his more experienced league peers, Leja would emerge as a power hitter. He hit cleanup after right-handed slugger Deron Johnson, hitting 22 HRs and leading the league in RBIs. His nickname was “Iron Liege,” after the thoroughbred that won the Kentucky Derby that year.

Leja displayed his fielding prowess, leading Eastern League 1st basemen in putouts, assists and double plays. Aspiring ballplayers could buy a Rawlings 3-fingered Frank Leja mitt called “The Claw.” He had started a lifelong friendship with a teammate, shortstop Clete Boyer.

The season had its sour moments, said Leja, when the Yankees cut his 1956 salary of $1,500 per month to $500. The front office said the prior poor season plus his annual bonus payment justified the reduction. (The bonus was paid in annual installments of $5,000.) After the 1956 season, Leja had married Anne Macarelli of Nahant, a small oceanfront town in Massachusetts.

In 1958, Leja was promoted to Double-A New Orleans. It was small consolation, because 5 of his Binghamton teammates were promoted 2 levels to AAA Richmond. Fellow demoted bonus baby Carroll played half the season in New Orleans as well. He observed, “Frank was a quiet guy and became fairly withdrawn. They didn’t like him and were punishing him.”

Leja would play in every Pelicans game, he would lead the team with 29 HRs and 103 RBIs and was the Southern Association’s top fielder at 1st base. His OPS of .866 helped him earn an invitation to spring training with the Yankees in 1959. Leja was still getting the cold shoulder, though. In St. Petersburg, Coach Johnny Neun, a former 1st baseman himself, was working with players at that position and invited them to ask for help. When Leja stepped forward, Neun said, “Well, if you don’t know how to play the bag by now, you’ll never know.”

Near cutdown day, Stengel told Leja his hitting and fielding were solid, but he was being sent to Richmond to teach him how to slide.

Leja hit for power (23 HRs) foR AAA Richmond, despite Parker Field’s deep fence in right field. He teamed with Johnson to produce 1-3rd of the team’s RBIs. At 1st base, Grba said Leja was “agile.”

On July 25th, Moose Skowron broke his arm and be out of the rest of the season. Leja remembered the New York press anticipating his callup. Instead, Clete Boyer was promoted and said to Leja, “Jesus Christ, I feel bad for you.” While Skowron was out, catcher Elston Howard and Marv Throneberry played 1st in New York. At the time of Boyer’s callup, Throneberry was hitting .185 with 3 HRs. After his career, Leja learned that the Yankees refused to trade him to the White Sox in 1959 despite Team Owner Bill Veeck’s offer of cash to repay Leja’s bonus and salary, as well as 3 AAA players. Instead, the pennant-winning “Go-Go Sox” would acquire veteran 1B Ted Kluszewski that August.

In 1960, Leja nevertheless said, “I would take the bonus money again.” He noted that it had paid for 4 years of mental health treatment for his mother. He also bought his parents a house and a car, said his son.

A serious hamstring injury in spring training dropped Leja to Double-A Amarillo. He told the Yankees, he’d recover faster in Richmond, with its better staff and medical equipment. Leja reported to Amarillo reluctantly, after staying at home for 2 weeks, but his injury resulted in a .203 average and 1 HR in 19 games.

He threatened to go home again, so he was loaned to Nashville, a Double-A affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds. After another lackluster 54 games and continued exasperation, he was loaned and demoted again to the Single-A Charleston White Sox. He would hit .211 in 36 games. In Richmond, 1st baseman John Jaciuk would played a full season and hit just 3 HRs with 42 RBIs. Though Leja’s 1961 player contract directed him to report again to Amarillo, he had persuaded the Yankees to let him go to spring training with AAA Richmond. He would make the team, but he still sat on the bench. Frustrated again and ready to quit, he was sold to the Syracuse Chiefs, a Triple-A farm team for the Minnesota Twins.

1961 Cardinals Player Photo

Rejuvenated, Leja would hit 30 HRs (2nd in the International League) with 98 RBIs, posting an OPS of .873. Again, he led the league’s 1st basemen in putouts, double plays, and assists. But when the Twins wanted to add Leja to their MLB roster, they were blocked. The Yankees said that they had still owned Leja’s rights. He called the commissioner’s office, but Frick refused to help. The day before the Yankees would open the 1961 World Series, they would trade Leja to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Ahead of the 1962 NL season, “it seemed as if I had a thousand pounds lifted off my shoulders,” Leja remembered. “I had never enjoyed spring training as much as I did that year. I was hitting the ball well and picking up Bill White at 1st base.” He was told he would platoon with White. Although St. Louis had traded away Joe Cunningham not long after acquiring Leja, Stan Musial and Gene Oliver could play the position too. The job competition also included Fred Whitfield and another former bonus boy, Jeoff Long.

1962 Angels Player Photo

Thus, 12 days before the start of the season Leja was sold to a 2nd-year expansion club, the Los Angeles Angels. Manager Bill Rigney assured him he would play. After 19 games, Leja had started 4 times and was hitless in 16 at-bats. On May 5th, he was traded to the Milwaukee Braves. He was sent to Triple-A Louisville and was advised that the Braves would be looking for a replacement for veteran 1st baseman Joe Adcock after the season. Leja would hit 20 HRs, tied for 4th in the American Association and was 9th in RBIs, despite missing 20 games. His defense at 1st base earned him the Silver Glove award, given to the top defender at all minor-league levels.

Teammate Phil Roof said, “Leja was a veteran, funny, had a big bat, big swing and was good at 1st base. I looked up to him as a 21-year-old. He calmed things down.”

In 1963, the Braves sent Leja to their new top affiliate, the Toronto Maple Leafs (International League). There he would play in 97 games and hit .240 with 17 HRs. In February 1964, just before spring training, Leja was released at age 28. He started making phone calls and sending letters to major-league teams and 1 team in Japan. There was no interest.

“Baseball is strictly a cold, cold business with a bad side I never dreamed of when I was a kid,” he said. “If either my ability or my attitude kept me out of the majors, why wouldn’t a single person tell me? I’d rather have someone tell me I’m no damn good than fight the maze of compliments I’ve received.”

In 1965, the Yankees started the season poorly and one analysis attributed their decline to the team’s awkward pursuit of bonus babies, using the rule too sparingly, and in the case of Leja (and Carroll), hindering their development.

In Nahant, where he and his family had made their home, Leja sold insurance year-round. Some days his baseball story was an asset and he was philosophical. At other times he wrestled with his memories. He wore his Yankees 1955 American League championship ring regularly with both pride and disdain, sometimes spitting at it.

In 1978, Leja said, “I’m convinced I was a marked man with the Yankees because I rebelled a little.”

Leja and Anne raised their 3 sons, Frank Carl, Gary and Eric in Nahant. The boys shared their father’s passion for competitive sports. Eric played college hockey at the University of Denver.

Frank Carl, the oldest and also left-handed, connected with Eddie Stanky, Baseball Coach at the University of South Alabama. Stanky, who had been in the Cardinals’ front office. when Leja was acquired from the Yankees, offered a scholarship to Frank Carl.

After 2 years at South Alabama, Frank Carl signed with the Red Sox as a free agent. Although he was released at the end of spring training in 1979, left-handed batting practice pitchers were hard to find, so he was hired to throw batting practice to the Red Sox and visiting teams at Fenway Park.

Gary had played college baseball and football at the University of Mississippi and baseball at the University of South Alabama (although Stanky had retired). He was signed as a free agent by the Cardinals in 1988, was invited to spring training, but he was later released.

At the 25th reunion of the 1955 Yankees in 1980, as Frank Carl remembered hearing, Team Owner George Steinbrenner assured Leja, “Your career means as much to me as Mickey Mantle’s.” Frank Carl emphasized how much that recognition meant to his father.

In 1982, Leja had left insurance sales and founded the L&L Lobster Company. He and his sons hauled traps by hand from the Atlantic Ocean in an open motorboat, which they moored at their bayfront home. “‘I should have gotten into this years ago,’” Frank Carl recalled his father saying. “He was happier selling lobsters.”

Still, 35 years after Leja insisted he was underpaid in 1954, he pursued it again. In 1989, he had asked the Major League Baseball Players Association to review his original contract. He said that his original inquiry had branded him a “troublemaker,” and it “had a direct bearing on my career.” Upon review, the MLBPA said it appeared that he was properly paid.

Carroll, who started just 2 games in 1955 and 1956 as a Yankee bonus baby, understood Leja’s frustration about his below-the-minimum contract. “Baseball made up the rules as they went along and would change them when enough owners complained,” he said.

In 1991, at 55, Leja had suffered a fatal heart attack. At the funeral, Clete Boyer sat with Frank’s widow. Leja’s obituaries could not capture his final reflections and how his family tried to come to terms with his bittersweet story.

Just prior to his death, Leja said, “This may sound bitter…It is bitter, but the pleasant memories were playing with the guys. It’s what happened to you as an individual. It’s the business side of it [that was difficult].”

“The Yankees lied. You never knew who wanted you because they always said, ‘Nobody wants you.’ How the hell do you know who wants you? If they put you on waivers and somebody claims you that they don’t like, then they can take you back off waivers.”

“So, they [the Yankees] ran the whole show. I mean baseball, not just the Yankees, but baseball. It was the same with any organization. That’s what you lived with. You became their pawn and you lived your life the way they told you to live it. So, if somebody had a hard-nose for you, they could bury you, and wouldn’t know which end was up,” he concluded. He also revealed that his bonus was not 6 figures but only $25,000.

Two decades later, in 2014 the Yankees themselves told Leja’s story, titled “Out at First.” His 1955 teammate, fellow bonus baby Tommy Carroll, confirmed, “Stengel didn’t like him at all. Frank and I were both prisoners,I don’t know what Frank was supposed to do, but whatever it was, he didn’t do it in Casey’s mind.”

The front office’s dismissive treatment of Leja, said Carroll, was consistent with the personality of General Manager Weiss. “He was a horrible person,” said Carroll, “The most miserable person you’ll ever meet.”

Stengel said, “They can’t even play once in a while because they don’t know anything except the size of their bank accounts an’ how much the newest cars cost, an’ how fast they are, an’ what town has the biggest steaks. But we gotta keep them on our benches.”

The story hurt again but 60 years later, not in the same way. “He never really spoke about the bitterness, unless people asked him about it,” Frank Carl said. “I never felt like he was bitter one day in my life. I think he learned to compartmentalize that part of his life. He kept it very quiet.”

“I think that my Dad was very proud to have been a major league baseball player, especially a Yankee,” the younger Leja added. “Although it didn’t turn out for him, he was a member of an elite group.”

And that’s how he will always be remembered. On Leja’s grave marker in Nahant, where he is buried with his wife, engraved in bronze is the interlocked “NY” representing the New York Yankees.

|

|

|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 6, 2024 15:07:32 GMT -5

Former Yankees Bonus Baby Infielder Tom Carroll (1955-1956)Compiled by Clipper INF Tom Carroll Yankees Spring Training Photo INF Tom Carroll Yankees Spring Training Photo

Thomas Edward Carroll Jr. was born on Sept. 17,1936, in Jamaica, N.Y., and grew up in the Queens suburbs. A fan of the Yankees and Joe DiMaggio, Carroll had played baseball at Bishop Loughlin High School in Brooklyn. He had played on semi-pro teams in New Jersey before attending Notre Dame. After signing with the team he grew up rooting for, Carroll returned to South Bend each fall, eventually completing his degree, 1 semester at a time, in 1961.

He was signed by the Yankees during his sophomore year at the University of Notre Dame. Carroll was a “bonus baby,” a player signed for more than $4,000 (reports on his bonus varied from $35,000 to as much as $60,000), who was then required to be on the Major League roster for 2 seasons before he could be sent to the Minor Leagues. A shortstop, who had hit .550 as a freshman, Carroll was billed as the heir apparent to 36-year-old shortstop Phil Rizzuto. The Yankees even announced the signing with both players present on January 28,1955.

"I’ve completed a cycle," Paul Krichell, the Yankees MLB Scout, who signed both players, said, according to the Associated Press. “Not only did I sign the greatest shortstop in Yankee history [Rizzuto], but I believe I have signed his successor [Carroll] for many years to come. Also, I have signed the shortest and tallest shortstops in Yankee history.”

Phil Rizzuto was listed at 5-foot-6, while Carroll was 6-foot-3.

1955 Topps Baseball Card

Carroll would appeared in his 1st big league game on May 7th. He was the 9th-youngest player in the American League that season. Like many of his fellow bonus baby earners, he spent most of his time sitting on the Yankees bench and watching the game, because Yankees Manager Casey Stengel had no use for them (Carroll and 1B Frank Leja), he would prefer to use his veteran MLB players instead. Occasionally, he would be used as a pinch runner (33 times over the 2 seasons, he was forced to spend 2 years in the majors due to the bonus baby rules of the time). Carroll was 19 years and 14 days old on October 1,1955, when he pinch-ran for veteran PH Eddie Robinson, who had hit for starting pitcher Johnny Kucks in the 6th inning of Game 1 of the 1955 World Series against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field. Carroll was stranded on 1st base, when the next 2 Yankee batters flied out to end the inning and Reliever Rip Coleman came on to pitch. Carroll again ran for Robinson the next day in Game 2, but he was forced out when Billy Martin grounded into a double play, with Hank Bauer replacing Carroll, when the Yankees took the field in the bottom of the 8th. He would later call this the greatest thrill of his short MLB playing career.

He remains the youngest player to appear for the Yankees in a World Series game and the youngest to do so for an American League team; only Hall of Fame Fred Lindstrom has played in the Fall Classic at a younger age. In 1956, he was still forced to stay in the bigs, he was the 10th youngest player in the league at 19. The Yankees again would reached the World Series in 1956, although Carroll's contribution to the success was minimal, and he was not used in the victory over the Dodgers.

Carroll had appeared in 14 regular-season games with New York in 1955, starting only the last game of the season, the 2nd game of a doubleheader at Fenway Park in Boston on Sept. 25th. He would play shortstop and batted leadoff, going 1-for-4 with a strikeout. For the 1955 AL season, he had 2 singles in 6 at-bats.

In 1956, Carroll would total 6 hits, all singles in 17 at-bats that year. In 50 games over 2 seasons, Carroll had entered a game as a pinch-runner 33 times and played in the field in only 16 contests. For 2 seasons with the Yankees appearing in 50 MLB games, while hitting .348 with No HRs and RBIs.

With his bonus baby time expired, he would spend the next couple of seasons playing in the Yankees farm system. Originally signed as a Shortstop, he was judged too tall for the position at 6' 3"; Tom was moved to 3B. In 1957, while playing for the AAA Richmond Virginians (International League), where he would hit only .213 with 13 HRs and 63 RBIs in 137 games, although he would show some power. It is not surprising that Carroll was somewhat overmatched; as the league's caliber of players was quite high with his pro experience up to that point had been very minimal. Seeing this, the Yankees would send him down to their AA team, the New Orleans Pelicans (South Association) at the start of the 1958 season, after which he was promoted to the AAA Denver Bears (AA); overall, he would hit a combine .283 with 7 HRs and 46 RBIs in 129 games that season.

1959 Topps Baseball Card

However, his pro baseball career was derailed once again, when he had to spent 6 months in military service for the Army after the 1958 AL season had ended; slowing down any momentum, that he was starting to build up. On April 12,1959, he was traded by the Yankees to the Kansas City A’s along with Minor League OF Russ Snyder for OF Bob Martyn and INF Mike Baxes. He would played little for his new team, hitting .143 with No HRs and 1 RBI in 14 games, however by early June, he was back playing in the Minor Leagues. Also, he played in the winter leagues in Venezuela during those years, but he had failed to develop any more as a prospect. After spending the entire 1960 season in the Minor Leagues, Tom would retire from baseball. Overall, Carroll was a poor fielder, he had a career fielding percentage of .905, but he finished his brief MLB playing career with a .300 BA in his limited playing opportunities.

He would graduated magna cum laude from the University of Notre Dame in 1961, a year after retiring from professional baseball. Then he would joined the Central Intelligence Agency as an Operations Officer, eventually earning Chief of Station duties, Senior Intelligence Service rank and the Intelligence Medal of Merit. Carroll would served in the CIA for 26 years, including overseas postings at embassies in Brazil, Chile, Venezuela and London, England. He subsequently worked as a Consultant into the early 2000s. On September 22, 2021, Tom Carroll would pass away at the age of 85. He was survived by his wife of 61 years, Joan; a brother, John; 4 children Catherine, Michael, John and Jean; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

|

|

|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 6, 2024 18:16:45 GMT -5

Yankees Reserve 1B/OF Marv Throneberry (1955,1958-1959)

This article was written by Alan Raylesberg, Edited by Clipper

1958 Topps Baseball Card 1958 Topps Baseball Card

Marvin Eugene Throneberry was born to be a Met. His very initials-MET-said so. As a member of the original 1962 New York Mets, Marv Throneberry’s colorful exploits (both good and bad) earned him the nickname “Marvelous Marv.” While remembered as much for his gaffes as his clutch performances, Throneberry had carved out a 7-year career in the Major Leagues. In 1962, while playing regularly for a Mets team that may have been the worst in history, Throneberry had his best season. He would hit 16 HRs, several of them in dramatic fashion. He became a legend in his own time, went on to become well known in commercials for Miller Lite Beer and even had a rock band named after him.

Marv Throneberry was born on September 2,1933 in Colliersville, Tennessee, a rural community 30 miles east of Memphis, with a population of approximately 1,000 people. Throneberry grew up in the nearby town of Fisherville, along with his older brother, Faye. Two years older, Faye would make it to the big leagues before Marv and played for 8 years. Theirs was one of more than 350 brother combinations, who have played major league baseball.

Marv and Faye’s parents were Walter Hugh Throneberry (1902-1946) and Mary Alice Callicut or possibly Callicutt (1903-1993). Walter and Mary Alice were married in 1922. A year later had the 1st of their 3 sons, Walter (1923-2000). The Throneberry boys were farm boys, growing up on the family farm in Fisherville. They also had a sister, Lurlene. Marv had lived in Fisherville, his whole life, passing away there in 1994, from cancer at the age of 60. Throneberry married Dixie Morton, a native of Rossville, Tennessee, who had their 1st child, a daughter, while Throneberry was still in high school. They would eventually have 3 daughters and 2 sons. When Dixie had passed in January 23,2016, at the age of 81, she had 11 grandchildren and 15 great grandchildren.

Marv Throneberry was a star baseball player at South Side High School in Memphis, where he twice made the All-City team. In 1952, he had signed with the Yankees after turning down an offer from the Boston Red Sox, the team that brother Faye then played for. Throneberry received a $50,000 signing bonus, a large amount in those days.

Although, Throneberry is best remembered for his sometimes magical, sometimes comical, 1962 season with the Mets, long before that he was a minor league phenom of whom great things were expected. A feared slugger in the minor leagues, Throneberry would hit 16 HRs in just 88 games during his 1952 pro player debut season. He would hit 30 HRs more in 1953 and 21 HRs in 1954. Then, playing for the AAA Denver Bears in the American Association, he would hit 36, 42 and 40 HRs in consecutive seasons (1955-1957) to lead the league in each of those years. He was named the league MVP in 1956. After playing 1 game for the Yankees in 1955, Throneberry made it to the MLB for good in 1958, playing for the Yankees and then the Kansas City Athletics and the Baltimore Orioles before finishing his MLB playing career with the Mets in 1962 and 1963.

Despite a swing that some compared to Mickey Mantle, Throneberry never had the success in the majors, that he had in the minors. The husky (6 feet, 190 pounds)10 left-hand hitter was considered a “can’t miss prospect,” slated to replace the aging veteran Joe Collins as the Yankees’ 1st baseman either in a platoon with Bill “Moose” Skowron or as a regular, with Skowron moving to 3rd base. While Throneberry had his opportunities, Skowron’s presence kept him from getting significant playing time and he never realized his apparent potential.

After his 1-game appearance with the Yankees in 1955, Throneberry was expected to compete for a roster spot the following season. Yankees farm boss, Lee MacPhail described him as “an up-and-coming 1st baseman [who] has vastly improved in the field” and “is not very far from a Yankees job.” He showed his flair for the dramatic in spring training when he hit a 3-run HR with 2 out in the 9th to tie a game at 4-4. Despite those heroics, Throneberry would return to the minors for the 1956 season.

The then 22-year-old Throneberry continued to figure in the Yankees plans. Famed Yankees MLB Scout, Tom Greenwade (who signed Mickey Mantle), called Throneberry “the most improved player in the American Association.” His American Legion coach, Lew Chandler, said that Throneberry “had the best potential of any kid I worked with. He was fast, he could throw and hit. He didn’t field too well, but he kept learning. He kept hitting around .500 for me and I knew his fielding would come.” After his MVP season in 1956, other teams had inquired about Throneberry’s availability. The Yankees, however, were invested in Throneberry; he went to spring training in 1957 “with high hopes of taking Joe Collins’ job as 1st sacker against righthanded pitching.” In a poll of major league farm bosses, Throneberry finished tied for 3rd in voting for the “best prospects to make the major leagues” and The Sporting News listed him as one of several rookies with a “can’t miss tag.” Yankees skipper, Casey Stengel, said that “all this boy needs is a little more polishing.”

The New York Yankees Yearbook touted Throneberry as one of the entries in “the 1957 rookie sweepstakes.” The Yearbook noted that the coaching staff “will concentrate on cutting down his strikeouts” which had “improved” from 150 times in 1955 to 132 times in 1956.

When Bill Skowron had fractured his thumb in spring training, the way was paved for Throneberry to win the 1st base job. Manager Stengel remarked that “Throneberry has made a splendid impression on everybody, and if we wanted to listen to trade conversation, he would be in big demand”. Unfortunately for Throneberry, he reported to spring training with a sore arm that did not heal and he was returned to AAA Denver, disappointed not to make the cut. The Yankees of the 1950s were loaded with talent, in the midst of Casey Stengel’s incredible run of 10 pennants in 12 years along with 7 World Championships. The reserve clause bound Throneberry to the Yankees, “although he [was] good enough to make almost any other major league club.”

As the 1958 season approached, with the Yankees having failed to win the World Series in 2 of the prior 3 years (at the time a major disappointment), changes were in order and young players like Throneberry could no “longer be detoured.” With Skowron having back issues and the Yankees needing a left-hand hitting 1st baseman, Throneberry had a “tremendous opportunity” to finally win a roster spot. The now 24-year-old Throneberry, frustrated in his inability to crack the Yankees’ deep roster, said that he hoped to be traded if he did not make it this time around. “It’s great to be a Yankee but not in the minor leagues,” he said. Throneberry, confident in his abilities, noted that he had played Winter Ball in the Nicaraguan League at his own request, “for the sole purpose of correcting his weakness swinging at bad pitches” while also noting that “I guess I’m doing all right as a fielder, since I finished up with the top average for 1st basemen in the American Association.” With Joe Collins now retired, the opening was there and Throneberry took it, becoming a member of the 1958 Yankees.

After seeing considerable playing time in May substituting for an injured Skowron, Throneberry ended up with a part time role in 1958. He would appear in 60 games, often as a pinch hitter, while starting 35 games at 1st base and playing 3 games in the outfield. While Throneberry had hit a disappointing .227, he did hammer 7 HRs in only 150 at-bats. His flair for the dramatic was in evidence on May 22nd, when he hit a HR in the 9th inning to give the Yankees a win over the Detroit Tigers.

Going into the 1959 AL season, the Yankees Yearbook noted that Throneberry “showed flashes of that great [minor league HR] power with the Yanks last year, but a strikeout tendency limited his 1st base and outfield duty.” While Stengel praised him in spring training for “hitting hard and fielding with class in right field,” Throneberry started only 44 games, 34 of them at 1st base and the rest in the outfield. He was often used as a pinch hitter and batted .240 with 8 HRs in 192 at bats.

With no regular position for him on the Bronx Bombers, Throneberry was traded to the Kansas City Athletics after the 1959 season had ended. It was one of the more memorable trades of all time, the one that brought Roger Maris to the Yankees. Casey was sorry to see Throneberry go, aware that “he could easily be giving up a potential slugging champion of the American League.” Stengel pointed out “he has to play every-day, he never had a proper chance with us. How could he, with Bill Skowron ahead of him at 1st base? But if Marv gets to work all through spring training and then plays regularly, he might be one of the top long-ball hitters in the league.”

1960 Topps Baseball Card

Throneberry had his moments with the Athletics, continuing to demonstrate his power with a flair for the dramatic. On September 25,1960, he hit a pinch-hit Grand Slam HR to beat Detroit. For the 1960 AL season, he would hit .250 with 11 HRs and 41 RBIs as the A's 1B. On May 19,1961, he would drive in all 4 Kansas City runs, including with a 3-run HR, in a 4-3 win over Minnesota. After playing in 104 games in 1960 and 40 in 1961, the Athletics had traded Throneberry to the Baltimore Orioles for Outfielder Gene Stephens. While hitting only .238 for the Athletics in 1961, Throneberry had 6 HRs and 24 RBIs in only 130 at bats. He hit 5 more HRs in 96 at-bats for Baltimore.

Mets Player Photo

After playing 9 games for the Orioles in 1962, Throneberry was traded on May 9th to the Mets for a player to be named later. Writing in The New York Times, Robert Lipsyte said “Throneberry’s acquisition marks a radical departure from the Mets’ practice of stocking the club with vintage talent of limited durability, but crowd-drawing appeal.” Lipsyte remarked that Throneberry’s “major league promise has always been considerably louder than his bat,” adding that as a Yankee he “was unable to dislodge Bill (Moose) Skowron at 1st despite his size…good arm and considerable speed afield.”

It was Casey Stengel, now manager of the Mets, who brought Throneberry back to New York, hoping to tap the slugger’s unrealized potential. The acquisition of Throneberry by the Mets was also historic as he became the 1st player to play for both the Yankees and the Mets.

The 1962 Mets, managed by the colorful Stengel, were an expansion franchise as National League baseball returned to New York following the departure of the Giants and Dodgers after the 1957 NL season. Those Original Mets won only 40 games and lost 120.

Their ineptness, including the unique way that they lost many of their games, made them a lovable, popular, team that drew nearly 1 million fans to the old Polo Grounds. Many books have been written about the 1962 Mets. The title of columnist Jimmy Breslin’s classic 1963 book, Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? said it best. No player symbolized that team more than Throneberry. He won several games with dramatic hits. Yet, his base running and fielding (17 errors at 1st base in only 97 games) left much to be desired and from that the Throneberry myth was born.

In his 1964 book, The Amazing Mets, New York sportswriter Jerry Mitchell wrote “name any game after [Throneberry came to the Mets] and Marv probably bungled a play in it with disastrous results or did something on the field or on the base paths that made strong men blanch. He had the knack.” Mitchell wrote that one of his “weaknesses was a baseball in his hands when the play was somewhere other than 1st base, with which he was fairly familiar.”

As a Met, Throneberry displayed the power that once made him a top prospect. Playing in the Polo Grounds, with its odd dimensions and very short right field fence; Throneberry hit 12 of his 16 HRs before the home crowd. His biggest hits came in the most dramatic moments.

His legend began to grow on July 7,1962 in the 1st game of a doubleheader against the Cardinals. Stepping in as a pinch hitter with 1 out in the bottom of the 9th and the Mets trailing by 1 run, Throneberry slammed a 2-run HR to win the game 5-4. On August 21,1962, Throneberry once again pinch hit a game-winning HR in the bottom of the 9th. Adding to the drama was the fact that Throneberry was coaching at 1st base as the inning began. The Pirates took a 4-1 lead into the bottom of the 9th. The Mets had 1 run in and 2 runners on with 2 out when the fans started chanting “We Want Marv! We Want Marv!” Casey obliged, taking Throneberry from the coaching box and putting him up to pinch hit. Facing the Pirates star reliever, Elroy Face, Throneberry proceeded to hit a 450-foot HR deep into the stands in right center field to win the game as the crowd went wild.

Throneberry had some good moments in the field as well. At the start of the 1963 season, New York Times columnist Arthur Daley looked back at the season that made him Marvelous Marv. Daley wrote about a game on August 24,1962, when the Mets surprisingly were beating Don Drysdale and the Dodgers, 6-3, going into the 9th inning at the Polo Grounds. Maury Wills led off and hit a twisting grounder down the 1st base line. “Throneberry fielded it like Hal Chase and made a great stop and greater toss to Jay Hook, covering the bag. He did the same on the fleet Junior Gilliam.” Willie Davis was up next and he hit a hard liner down the right field line but “Throneberry went 10 feet in the air to spear the liner and landed on the flat of his back, the ball still in his glove.”

Great fielding plays by Marvelous Marv were the exception and not the rule, however. On Casey Stengel’s birthday, the Mets Manager received a birthday cake. Throneberry asked Stengel “Why didn’t they give me a cake on my birthday?” to which Stengel replied “We was afraid you’d drop it.”

The most famous Throneberry story involved his fielding and base running miscues in the 1st game of a double header against the Chicago Cubs on June 17,1962. In the top of the 1st inning, Throneberry botched a rundown play, when he blocked a runner trying to get back to 1st base and was called for obstruction resulting in the runner being safe. Then, in the bottom of the inning with the Mets already trailing 4-1, Throneberry appeared to make up for the botched play, when he hit a triple driving in 2 runs, only to be called out on an appeal play, because he missed 1st base. As the story goes, Stengel came out to argue the call but was told by the umpire “Don’t bother, Casey, he missed 2nd base too.” In a fitting end to the game, the Mets were trailing 8-7 in the bottom of the 9th with the tying run at 1st when Throneberry came to bat with a chance to tie or win the game. He struck out.

When Throneberry 1st joined the Mets, he had replaced an ailing Gil Hodges at 1st base. Replacing the Brooklyn Dodgers legend, as Throneberry struggled in the field, led to some boos from the Polo Grounds faithful. As the season went on, the balding, round-faced Throneberry turned those boos to cheers as his dramatic hits, self-deprecating sense of humor and folksy “everyman” manner made him a fan and media favorite.

August 18,1962 was "Stan Musial Day" at the Polo Grounds as the Mets honored the National League legend. Yet, it was Throneberry’s fans who stole the show that day, wearing their “VRAM” T-shirts (“Marv” spelled backwards) and chanting his name to the point that an embarrassed Throneberry said “I hated to take the play away from Stan on his big day here.” Throneberry received more than 100 letters a day that season and had his own Fan Club with approximately 5,000 members. His legend grew to the point that a chapter in the 1964 book," The Amazing Mets", was simply titled “Marvelous Marv.” His popularity was so great that the back cover of Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? promoted the book with the caption “THE ‘M’ BOYS” stating “Not Maris. Not Mantle. Not Mays. It’s Marvelous Marv Throneberry and the mad, mad, mad, mad Mets.”

Prior to the 1963 NL season, Throneberry did not get the pay raise he was seeking from Mets General Manager George Weiss and the dispute led to Throneberry holding out during spring training. The Mets had acquired a young 1st baseman, Tim Harkness, from the Dodgers and also they had 18-year-old Ed Kranepool, fresh out of James Monroe High School in the Bronx, to play 1st base. With the position suddenly crowded, after Throneberry had batted 14 times with only 2 hits in early season action, the Mets sent him to their AAA Buffalo Bisons (IL) farm team on May 9th. According to the New York Times, Throneberry “seemed completely depressed and angry” about the demotion. “I may be back sooner than a lot of people think”, he said, “I’m going to leave my name up there above the locker.” As the Times reported, all the other Mets lockers had a hand-printed card containing the uniform number and last name of the player. Throneberry’s card did not. Rather, it said simply “Marvelous Marv.”

Manager Stengel said, “I hope he hits 25 or 50 HRs down there, so I can pull him back quick.” It was not to be. Throneberry would never return to the Major Leagues. After playing 8 games with Buffalo in 1964, his professional baseball career was at an end.

The mark he made on the Mets and New York baseball lived on long after he retired. “Twenty-five years after he was gone, you would still see in the crowd -V-R-A-M- which was Marv spelled backwards”, said Dixie Throneberry, Marv’s widow. “And in the crowd, they would chant “Cranberry, Strawberry, we still want Throneberry.”

After he had retired from baseball, Throneberry became well known for his role in humorous commercials for Miller Lite beer, in which he appeared with star athletes including Billy Martin. The commercials would end with Throneberry saying tongue in cheek “I still don’t know why they asked me to do this commercial.” There was at least one commercial featuring him alone where his punch line said it all: “If I do for Lite Beer what I did for baseball, I’m afraid their sales will go down.”

Throneberry’s fame was far greater than that of an ordinary .237 lifetime hitter. When he had passed away in 1994, George Vecsey devoted a column to “Marvelous Marv” in the New York Times. Vecsey wrote that Throneberry “never wanted to be a lovable icon of ineptitude, but after it happened, he went along with it. He was Marvelous Marv, the ultimate Met.” “Marv missed bases. Marv dropped throws. Marv threw to wrong bases. Marv missed signs,” wrote Vecsey, noting that Throneberry came to embrace what made him famous. Throneberry would “tag along with all the superstars” in the Miller Lite commercials and would then drawl his famous and funny line about not knowing why they asked him to do the commercial. Explained Vecsey, “It meant that one of the hip fans from the Polo Grounds had made it to Madison Avenue and was using his 1962 Met-type humor to honor Marvin Eugene Throneberry, who was, in his own weird way, a star.”

Throneberry was proud of his career in baseball, telling a reporter “Hey, I really wasn’t that bad a ballplayer. I always thought I was a good ballplayer. I played in the major leagues, there are millions of ballplayers in this country not good enough to make the majors.” Asked why he did the commercials that made fun of his career, Throneberry said that he was “going to work just 2 times a month and making a great living. I can fish 4 or 5 days a week. I’ve got 5 boats and 5 motors. I don’t have to worry about things I used to worry about. I wouldn’t trade this for anything.”

Marv Throneberry holds a special place in the memories of Mets fans. As of December 2018, he is ranked on the “Ultimate Mets Database” as the 122nd most popular player out of 1,067. Fans post their memories of him on that database and the post that best captures what he was about was written by none other than his oldest son, Jody, who wrote in 2013:

My dad had many stories escalated about him and his career. Some true, some not. He was not bitter by any means about how people perceived him. He had a very large fan base for which we receive letters still to this day. He has a World Series ring and 3 years before that he led the [Denver] Bears to the championship. Casey and Billy saw something in my dad and obviously enjoyed having him around.

He must have been special to have over 5,000 fans wear shirts with VRAM on them. He truly loved his fans. I have watched him sit around hours on end and read fan mail and sign and return them to his fans.

In the last days of his life when suffering from terminal cancer, he would make it a point to sign as many cards as he could and have them mailed back out. That is the Marvelous Marv we all knew and loved.

The New York Mets have had a colorful history. Formed in 1962, the Mets were lovable losers for many years before miraculously winning the World Series in 1969. Since then, the Mets have had 4 other World Series appearances as well as long stretches as a losing team. On a franchise that has had Hall of Famers like Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan, Gary Carter and Mike Piazza, Marv Throneberry stands out, not for his statistical accomplishments but for his dramatic flair and good-natured sense of humor that allowed him to become known simply, and forever, as Marvelous Marv.

|

|

|

|

Post by inger on Feb 6, 2024 19:21:53 GMT -5

Now that this commercial is over, let’s get back to our regular programming. One more word from our regular sponsor, get SPAM today. The gelatinous treat that’s really neat, SPAM…

|

|

|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 7, 2024 20:28:33 GMT -5

Yankees Pitcher Rich Beck 1965This article was written by Joe Schuster, Edited by Clipper

1966 Topps Baseball Card 1966 Topps Baseball Card

At the end of the 1965 season, New York Yankees pitcher Richard Henry “Rich” Beck had every expectation of a good year ahead. For the Yankees’ Double-A franchise at Columbus, Georgia, he’d finished 3rd in the Southern League in ERA, earned a spot on the league All Star team and won 13 games, including a no-hitter, his 2nd as a professional. In the last game of the season, with the league title on the line, Beck shut out Asheville, 7-0, to clinch the pennant for Columbus by a scant .001. The Yankees rewarded him by calling him up to the major leagues for September; he responded by going 2-1 with a 2.14 ERA. In his second start—his first appearance at historic Yankee Stadium—he shut out Detroit, 3-0. Looking ahead to the 1966 season, Yankees Manager Johnny Keane said that Beck “figures pretty big for us in the future.”

1965 Topps Baseball Card

Beck, however, never made it back to the major leagues. In the offseason, with the US in the midst of the Vietnam War, he received his draft notice from the Army. In 1968, after a 2-year tour of duty, Beck, by then 28 years old, tried a baseball comeback, but found that he had lost his control on the mound. In 2 less-than-stellar seasons with Yankees and New York Mets Triple-A teams, he had posted a 5.41 ERA for the 2 seasons, giving up 189 hits and 123 walks in 178 innings, and then he was through.

Beck, who was 6-feet-3 and weighed 190 pounds in his playing days, was born on January 21,1940, in Pasco, Washington, in a heavily agricultural section of the state’s southeast corner. (For years, beginning before the Yankees signed him to a professional contract in 1962, he listed his birthdate as 1941, shaving a year from his age. In an interview with the author, he said the scout who found him for the Yankees, Eddie Taylor, said his being 21 would make him more appealing to the organization than if they knew he was 22.) His father, Henry, operated a mom-and-pop grocery, while his mother, Ragna (nee Overlie), stayed home to raise Beck and his younger sister, Beverly. Both his mother and sister died when Beck was 8 years old. Shortly after that, Beck’s father put him to work in the store after school and during the summers. He started out sweeping floors for 50 cents an hour; by the time he was 13 he was working as a checker and helping deliver orders to elderly customers.

“Pasco was a blue-collar town whose largest employer was the Northern Pacific Railroad,” Beck said. “A lot of our customers were railroad people who were paid once a month and so they’d charge their groceries all month long and then, when they got their checks, they’d come in, settle up, and most of them would turn around on that same day and buy their groceries on credit to start the next month’s tab.”

Beck had played football, basketball, and baseball at Pasco High School until he graduated in 1958. By his own assessment, he was a “very mediocre football player and okay at basketball.” He said he played those 2 sports primarily to stay in shape for his passion, baseball.

“I had always loved the game,” he said. Although he grew up before relocation and expansion took any major league-teams to the US west, he was a diehard Dodgers fan. As a young boy, he said, he spent hours a day playing baseball in his yard with a friend who was a Braves fan. “We would use a tennis ball in the driveway and play Dodgers-versus-Braves day after day, batting left- or right-handed depending on whose spot in the lineup it was.” That practice taught Beck how to switch-hit.

Beginning in Beck’s junior year, Eddie Taylor, the Yankees scout, began following him and, after Beck’s senior year, when he earned All-State honors as a pitcher, offered him a contract. Beck declined the offer because his father was adamant that he attend college.

“When my father was younger, he’d had the chance for a scholarship but had turned it down to help in the family store,” Beck said. “He never complained about that decision but he said it was important for me to get an education since it would open doors for me that he didn’t have.”

When his father was stricken with cancer soon thereafter, Beck, who said the 2 were close even before his mother and sister died, became even more determined to accede to his wishes that he attend college. He started as a mathematics major at Columbia Basin Community College and then he would transferred to Gonzaga University for the 1961-1962 academic year, switching his major to business administration with an emphasis in finance. There, he had played basketball for a mediocre team that went 5-9 and pitched and played 1st base for the baseball team. When his collegiate eligibility ran out, he would sign with the Yankees for a nominal progressive bonus that would pay him $1,000, if he reached Double-A ball and lasted at least 90 days there; if he lasted 90 days at Triple-A, he would get another $1,500, and if he reached the major leagues and stayed there for 90 days, he would get $2,500 more. Offering him a salary of $600 a month, the Yankees had assigned Beck to their Idaho Falls team in the Class C Pioneer League. In his 1st game, on June 19, he would pitch a 7-inning no-hit, no-run game against the Boise Braves, striking out 8 and walking 2. He would finish the season 9-6 with a 3.63 ERA, striking out 171 batters in 134 innings and walking 71.

In the offseason, the Philadelphia Phillies took Beck from the Yankees’ organization in the minor-league 1st year player draft. They would assign him to their Double-A Southern League team at Chattanooga. It was an all but lost year for Beck. In 4 games at Chattanooga– 2 starts and 2 relief appearances, he went 0-2 with a 7.50 ERA, while walking 18 and striking out only 12 in 18 innings. The Phillies would send him down to Single-A Bakersfield (California League). There, he started only 2 games (12 innings, 1-1, 4.50 ERA) before he became ill in early June with viral pneumonia that put him in the hospital for 3 weeks. When his high fever persisted, Beck’s doctors had advised the Phillies to sit him down for the rest of the year.

The next year, the Phillies would send Beck to Chattanooga again and, after a 5-0 start, he ended up 6-9 with a 5.38 ERA. That was nearly his last year in baseball. During the offseasons, Beck had continued his education at Gonzaga. After he had finished his degree in business administration, he had begun working in a bank, SeaFirst, in installment credit collections. Although he hated the job, it was a steady one, he said, with the promise of promotion within the bank. He had married Jeanne Elizabeth Moorman in 1960, while they did not yet have children, the prospect that they might prompted him to think about stability. “When the Phillies sent me a contract for the 1965 season, for $700 a month, I told them I had a good job with the bank and if they wanted me to sign the contract, I needed more money,” he said. “[General Manager] Jack Quinn just responded, ‘Either sign the contract or let us know you’re quitting so we can offer the spot on the roster to someone else.’ ” Beck decided to sign.“I thought I would give it 1 more try,” he said. “I decided just walking away would be throwing in the towel and I didn’t want to do that.”

On April 12,1965, the Yankees had reacquired Beck from the Phillies. They would send him to their Double-A Southern League team in Columbus, Georgia. For the 1st season since his initial one as a professional, he had pitched consistently well, winning his 1st 5 decisions. Before the Yankees called him up, the highlight of his season occurred in August 13th, when he pitched his 2nd professional no-hit, no-run game, against Lynchburg. Beck struck out 5 and faced the minimum number of batters; he walked 2, but they both were caught trying to steal.

In the last week of the season, Beck’s Manager, Loren Babe, told him that the Yankees were calling him up after the last game. (Columbus won the league pennant; there was no playoff.)

“We were in Lynchburg when he told me,” Beck said, “and I proceeded to go out and pitch a not particularly good game.” Beck, however, proved that he merited the Yankees’ interest by nearly single-handedly winning his next start, the final, decisive game of the season, pitching a 2-hit, 7-0 shutout against the Asheville Tourists and driving in Columbus’s 1st 2 runs with a second inning single. The victory gave Columbus its 1st league title since 1947.

After the game, Beck and his wife drove 700 miles to New York to meet the Yankees. Beck remembered clearly his first glimpse of life in the major leagues.

“When we got to New York, we checked into the Concourse Plaza Hotel and I walked the 6 blocks to Yankee Stadium,” he said. “Someone took me down to the locker room and I stashed my bag in the trainer’s room and walked out under the 1st-base stands into the dugout and took the 2 steps up onto the field level and stopped and looked from left to left-center to right, to the right-field wall and I thought about how I had seen this field so many times on television. I thought about how Lou Gehrig had played here and that Mickey Mantle plays here now. Then it struck me, ‘Oh my God, he’s my teammate, and so is Elston Howard and Whitey Ford.’ It was an overwhelming feeling, that I’d wanted to do this for my entire life and there I was.”

In 1965, a year removed from what turned out to be their last pennant until 1976, the Yankees were having a miserable season, when Beck joined them. While they had won the American League title the previous 5 years and 9 of the previous 10, they were then in 6th place, 19 games out of 1st and 10 games behind 5th-place Detroit. The Yankees brass had decided that September would be a month to find out who among the team’s young talent might be viable prospects for the next season. In addition to Beck, the team also called up pitcher Mike Jurewicz (who like Beck never played in a major-league game after 1965), 2nd baseman and future All Star Roy White, shortstop (later outfielder) and future All-Star Bobby Murcer and Outfielder Archie Moore, who had appeared in 31 games the season before and who, after going 7-for-17, (.412, 1 HR, 4 RBIs) in September 1965, also never again appeared in a major-league game.

A week after his call-up, on September 14th, Beck would start his 1st MLB game, against the Washington Senators in Washington.

The game was scoreless until the bottom of the 5th, when Washington got a run, on back-to-back hits, a double by infielder Ken Hamlin and a single by catcher Jim French. The Yankees tied the score in the top of the 6th and took the lead for good in the top of the 7th on Murcer’s 1st MLB career HR. (It was also his 1st MLB hit.) Beck ended up pitching into the 8th, when, after he allowed back-to-back singles to start the inning, Yankees Manager Johnny Keane sent Steve Hamilton in to relieve him. After Hamilton shut down the Senators and then Pedro Ramos closed the game with a scoreless 9th, Beck had his 1st major-league victory. His line: 7 innings, 1 run, 6 hits, 8 strikeouts and no walks. In its account of the game, the New York Times wrote that Beck “impressed as a strong prospect for a place on the starting staff in 1966 [and] showed a blazing fastball, a good curve and fine control.”

Beck started again 5 days later, September 19th, against the Tigers in Yankee Stadium. He was not quite as sharp as he was in his 1st game, allowing 9 hits and 5 walks with no strikeouts, but he ended with a 3-0 shutout, helped by 3 double plays. (“It may have been one of the ugliest shutouts ever,” Beck recalled). In his 3rd and MLB final start, against Cleveland on September 28th, Beck had lasted only 5 innings and took the loss, when Indians outfielder Rocky Colavito hit a 3-run HR in the 5th inning.”

After the season, with Keane and others in the Yankees organization talking openly in the press about Beck being one of their bright prospects, the Yankees sent him to their Florida instructional team. However, almost immediately, Beck had received his Army draft notice. The Yankees, not wanting to lose him for 2 years, found him a spot in an Army Reserve unit instead. But a new law prohibited anyone who had already received a draft notice from opting for the Reserve, Beck said. He spent a few weeks shy of 2 years in the Army, stationed as a payroll specialist at Fort Hood, Texas. During the 2 years his name showed up periodically in newspaper articles whenever the Yankees talked about which of their prospects might be able to help stop what was becoming a serious post-glory funk; in 1966, the team finished last and in 1967 the Yankees ended the year 9th out of 10 teams.

Beck was such a significant figure in the Yankees’ talks of their plans to turn the organization around, and near the start of spring training in 1968, Leonard Koppett of the New York Times wrote a long article about Beck’s possible comeback. But Beck didn’t make the club that spring, pitching the year in Triple-A with Syracuse Chiefs, going 5-5. Nor did he make it the next year. In fact, in early June of the 1969 season, when Beck was 0-5, the Yankees would release him. He quickly found another team. “We were facing the Mets’ Triple-A team in Tidewater on the day the Yankees let me go and so I walked (to the clubhouse) next door and said to Clyde McCullough, the Tidewater Tides Manager, ‘Do you need any pitchers?’ He asked, ‘Is your arm all right?’ and had me throw for 10 minutes.” The club offered Beck a spot on its staff and he finished out the season, going 4-1 the rest of the way, helping Tidewater win the International League title.

At the end of the season, however, the Mets had sold Beck to the Kansas City Royals and he decided that he had had enough. “We had a daughter then (Kate, who was born in 1968) and I decided I didn’t want to be a baseball bum,” Beck said. “In my 1st year in (Class) C ball, I had met a player who was 30 and still trying to hang on and I told myself I wouldn’t be him.” In the 2 seasons, that Beck had pitched after returning from the Army, his bases on balls per inning pitched rose. During his time in the Army, he said, his baseball activity consisted of nothing more than a few games of catch on the base.

“For me, it was that I had lost my fine tuning,” he said. “Instead of throwing the ball on the outside corner, it was down the middle. My arm didn’t hurt. I just wasn’t sharp. I didn’t want to feel like that on payday, I would have to back up to the pay window because I was embarrassed to be collecting a check when I wasn’t as effective as I thought I should be.”

After he had given up pro baseball, Beck worked in lending at Seafirst, until the bank had laid him off in 1986. He and Elizabeth were divorced in 1975. In August 1976, he had married Cheryl Roy. They had a daughter, Chelsea, born on Beck’s birthday in 1978, and a son, Lance, born in 1985, and 2 grandchildren. After leaving Seafirst, Beck worked briefly for a company that removed fiberglass insulation, in a company he and his wife ran that sold aloe-vera-based skin care products and for the A.C. Nielson Company, for whom he was a market supervisor. When the author spoke to him, in 2010, he was working as a substitute teacher in Spokane, Washington, where he was living.

Once, he said, the students in a class he was teaching learned that he had pitched briefly in the major leagues. “One of them asked me, ‘Mr. Beck, weren’t you really upset that you got drafted and lost out on your chance to keep playing ball?’ After we kicked it around the room a while, I told them, ‘I’m sitting here talking to you, but I was in the service with a lot of 18-year-old guys, who went to Vietnam and never came back and so I consider myself lucky. How many times does a person get to realize their dream? I didn’t get to realize it for very long, but I did get to realize it.”

Sources

Most of the information about Beck’s early life and his life after baseball, as well as his comments about his career, came from 2 interviews I had with him, on May 12 and June 8, 2010. A few of the details come from a player questionnaire Beck completed in 1965 and on file at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. For details of his minor- and major-league career, I referred to a number of newspapers, including The Sporting News, the New York Times, the Gastonia Gazette, Newsday, the Lawton Constitution, the Charleston Daily Mail, the Montana Standard Post, and the Spokane Daily Chronicle. I accessed most of the newspapers through the archives at newspaperarchive.com, and The Sporting News through the archives at www.paperofrecord.com/default.asp.

|

|

|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 8, 2024 21:23:43 GMT -5

Former Yankees Minor League 1st Baseman Bud Zipfel

Article Information was compiled by Clipper

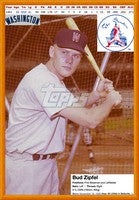

1962 Baseball Card

Marion Sylvester "Bud" Zipfel is a retired American pro baseball player, who had appeared in 118 games over 2 seasons in Major League Baseball for the 1961-1962 expansion "new" Washington Senators. He was a 1st baseman and left fielder, who batted left-handed, threw right-handed, stood 6 feet 3 inches tall and weighed 200 pounds.

On November 18,1938, he was born in Belleville, Illinois. After graduating from Belleville High School in 1956, 17 year-old Bud Zipfel would sign with the New York Yankees. He would steadily progress through the Yankees' minor league system, over the next 5 seasons, showing some potential as a powerful, left-handed-hitting 1st baseman. He would exceed the 20-HR mark twice, with the Class D 1958 Auburn Yankees in the New York-Penn League with 21 HRs and then with the Class A 1960 Binghamton Triplets in the Eastern League with 28 HRs.

On December 14,1960, the new expansion Washington Senators had originally drafted veteran New York Yankees INF Gil McDougald, but he refuses to go, citing his 10-year MLB player rights. Yankees will select Minor League 1B Bud Zippel to replaced him in the player draft. Bud Zipfel had an "impressive" spring training with the expansion Senators in 1961, after continuing his powerful hitting in the minor leagues; he had his best statistical player season in 1961, while playing for the AAA Houston Buffs (American Association), while batting .312 with 21 HRs and 62 RBIs in 101 games. Bud Zipfel would make his MLB player debut with Washington on July 26,1961 against the Twins. Bud would go 1 for 5 in the game with a single. He would remain on the MLB roster for the rest of the 1961 AL season as a backup 1st baseman to former Yankees 1B Dale Long, but he was less impressive with his bat; hitting just .200 with only 4 HRs and 18 RBIs in 50 games.

1961 Senators Player Photo

After the 1961 AL season had ended, Bud Zipfel was drafted into the United States Marine Corps, but he would completed his service time, just in time to rejoin the Senators at the end of their 1962 MLB spring training camp. He would begin the 1962 baseball season in the minor leagues with the AAA Syracuse Chiefs (International League), playing in 62 games; while hitting .258 with 13 HRs and 36 RBIs. On June 26,1962, Bud was recalled from AAA Chiefs to the Senators MLB roster. Zipfel would remain with the Senators for the rest of the 1962 AL season, splitting his playing time between 1st base and left field. Once again, he would struggle to hit MLB pitching, batting just .239 with 6 HRs and 21 RBIs in 68 games. The highlight of his 1962 AL season was a 16th inning HR (the last of his MLB playing career) that provided the winning margin in a game in which his Senators teammate, Starter Tom Cheney had struck out a MLB pitching record of 21 Baltimore Orioles batters in a 228 pitch complete game on September 12th. Cheney had pitched brilliantly in 16 innings of work, giving up only 1 run, while striking out a record 21 Orioles batters. Cheney had 13 strikeouts through 1st 9 innings in the game.

1963 Reds Player Photo

At the end of the 1962 AL season, the Senators would sell Zipfel's player contract to the Cincinnati Reds. For the next 4 seasons, he would play for the minor league affiliates at different levels of the Reds, Detroit Tigers, Philadelphia Phillies and the St. Louis Cardinals organizations. He was not recalled to the MLB teams during that playing time; after the 1966 baseball season had ended, he would retire from pro baseball. Bud Zipfel would finish his MLB playing career with a .220 BA with 10 HRs and 39 RBIs in 118 games. After his pro baseball retirement, he would have a successful business career in the Real Estate field.

|

|

|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 9, 2024 17:56:56 GMT -5

Spud Murray Yankees Batting Practice Pitcher 1960-1968

Compiled by Clipper

Meredith Warrington "Spud" Murray was an American Minor League baseball pitcher and a (MLB) Batting Practice Pitcher for 2 MLB teams. Murray was possibly the 1st full-time batting practice pitcher in New York Yankees history Meredith Warrington "Spud" Murray was an American Minor League baseball pitcher and a (MLB) Batting Practice Pitcher for 2 MLB teams. Murray was possibly the 1st full-time batting practice pitcher in New York Yankees history

Meredith Warrington "Spud" Murray was born on October 28,1928 in Media, PA. He was the son of J. Warrington and Elizabeth A. Murray. They had 2 other sons, K. Leroy and W. Ralph. He had had attended Media High School, where he had starred in baseball and basketball, ranking among the best players in Delaware County, Pennsylvania.

At age of 17, Murray was signed as an Amateur Free Agent with the Cleveland Indians. However, a pitching arm injury would limit his pro pitching career (1947-1955,1965). The Indians would sell Spud Murray to the independent Montgomery Rebels (South Atlantic League) in 1954. Murray would finish with a Minor League pitching record of 77-66 in 274 games. In 1965, he would appear in 1 game for the Florida Instructional League Yankees with a 0-1 record along with a 3.00 ERA.

Mayo Smith, the Manager of the Philadelphia Phillies, would hired Murray as his batting practice pitcher for the 1958-1959 NL seasons. He would join the New York Yankees in the same role 2 years later. He would hold this role with the Yankees until 1968. One of his more memorable seasons with the Yankees was in 1961, throwing to former Yankees greats Roger Maris, Yogi Berra and Mickey Mantle. Roger Maris would break Babe Ruth’s single season HR record by hitting 61 HRs. The Yankees would defeat the Cincinnati Reds, winning the 1961 World Series in 5 games.

In 1961 Yankees Spring Training Camp, he met Marylin Monroe and Joe DiMaggio

In 1980, Philadelphia Phillies Manager Dallas Green, an old friend from Spud’s minor league days with Cleveland, had asked him to pitch batting practice to win the team’s pitchers during homestands. The Phillies went on to win the 1980 World Series, becoming the 6th championship team that Spud was a part of. Spud Murray would live in Waterloo, Pennsylvania. He would enjoyed hunting and fishing, often going fishing with Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford. After retiring from baseball, Spud had worked in the Maintenance Department of the Ridley School district in Delaware County. He would pass away at age of 82 on September 15, 2011.

|

|

|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 9, 2024 17:58:15 GMT -5

Now that this commercial is over, let’s get back to our regular programming. One more word from our regular sponsor, get SPAM today. The gelatinous treat that’s really neat, SPAM… Thank you How do I report this kind of spam posting? Clipper |

|

|

|

Post by kaybli on Feb 9, 2024 18:18:20 GMT -5

Now that this commercial is over, let’s get back to our regular programming. One more word from our regular sponsor, get SPAM today. The gelatinous treat that’s really neat, SPAM… Thank you How do I report this kind of spam posting? Clipper If you see spam, hit the gear button to the top right of the post and then click "Report Post". |

|

|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 9, 2024 18:25:27 GMT -5

Thank you How do I report this kind of spam posting? Clipper If you see spam, hit the gear button to the top right of the post and then click "Report Post". Thank you! Also would it be possible to put the past This Week in Yankees threads in one thread, after they had expired for their week? That way the readers would see them in one place, sort of Yankees History Library for the Board. Clipper |

|

|

|

Post by kaybli on Feb 9, 2024 18:36:00 GMT -5

If you see spam, hit the gear button to the top right of the post and then click "Report Post". Thank you! Also would it be possible to put the past This Week in Yankees threads in one thread, after they had expired for their week? That way the readers would see them in one place, sort of Yankees History Library for the Board. Clipper Sure. I'll do that for you later tonight. |

|

|

|

Post by fwclipper51 on Feb 12, 2024 18:10:45 GMT -5

Pitcher Paul Hinrichs:

1st Yankees Bonus Signing

This article was written by Bill Nowlin, Edited by Clipper

Red Sox Player Photo

It was about a bad a brief outing as a pitcher could have, but at least it was mercifully short. Fortunately, there are other things in life that might have greater meaning than a bad outing on the mound.

It was at Comiskey Park, in Chicago, the Boston Red Sox were already down, 6-2, after 7½ innings in the 2nd game of a June 3, 1951, doubleheader against the White Sox. Boston had won the 1st game, 5-3, behind the pitching of Mel Parnell and Ellis Kinder, largely thanks to the 4 runs batted in by Vern Stephens on a double and a single, each hit driving in 2 runs.

Red Sox Manager Steve O’Neill had already pulled his starter, Chuck Stobbs, after 4 runs in 4 innings, and replaced reliever Bill Evans, who’d given up 2 more runs in the 1-plus inning that he had worked, Walt Masterson threw 2 scoreless innings but he was lifted for pinch-hitter Fred Hatfield, who doubled to lead off the top of the 8th and then scored on Dom DiMaggio’s single. That was it for the top of the 8th, though, and Paul Hinrichs was brought in to pitch the bottom of the inning, facing the 3-4-5 batters in the White Sox lineup. Paul

Hinrichs was a right-hander, listed at an even 6 feet tall and 180 pounds.